History of Chicago - Part 1: The Very Beginning

A look at the very beginnings of Chicago. From the glaciers to the Potawatomi.

Sixty miles away in Michigan, Chicago’s skyline juts out of the horizon like broken metal teeth. The silhouette of the skyscrapers seems to rise out of one of the world’s largest bodies of fresh water, Lake Michigan. It’s one of the most recognizable skylines in the world. The city of broad shoulders.

2.6 million people call Chicago home1. A city that has been a crossroads of cultures since its founding in 1837. History is etched into the city’s bones: buildings that survived the Chicago Fire, street names that honor the first residents of the city, and roads that follow the original trading trails the tribes of the area used. Chicago has been called the “Second City” for many reasons.

This series will explore the rich history of Chicago. From Fort Dearborn to Al Capone. The Great Depression to the Chicago Bulls’ dominance of the NBA. All of this city’s greatest achievements will be explored here.

But every story has a great beginning. Today, we start our journey at the very start. Before Joliet and Marquette discovered the Chicago River portage. Before the Potawatomi called Chicago home. We begin our story with ice.

Lake Chicago

12,000-13,000 years ago the last of a series of glaciers receded, revealing a land scarred by ice. The Wisconsin glacier plowed boulders into the Earth, flattening the ground and creating the plains of Illinois. Ice pushed rocks and shoveled out massive valleys. At the glacier’s height, it was nearly two miles above the ground. As the ice melted, water flowed into the newly plowed valleys, creating a series of freshwater lakes one day known as the Great Lakes, including Lake Michigan2.

Following the ice melt, a basin from Lake Michigan expanded as far west as the Des Plaines River, at the edge of Chicago’s modern city limits. The basin is recognized as Lake Chicago. A small ridge marked the shore of the lake, about 10 feet in height, it kept the area of modern-day Chicago submerged in 60 feet of water. Initially draining south into the Gulf of Mexico, the flow of the lake was reversed eastward, today’s natural flow of Lake Michigan3.

Lake Chicago slowly drained and its waves and currents smoothed its bottom. Clay left over from the glaciers made it difficult for the water to drain away. A swampy marshland took the place of the lake as Lake Chicago receded. The crescent-shaped ridge by the Des Plaines River is actually a continental divide. Water on the west of the ridge flows south into the Gulf of Mexico, on the east it flows into Lake Michigan, at least one river used to. Only one portage cut through the ridge. The Chicago River flowed into Lake Michigan as it snaked through a muddy marshland4.

Tall grass and reeds decorated the swamp. Pungent wild onions hugged the streams and rivers. The locals called this land šikaakwa, Miami-Illinois roughly meaning “skunk-onion.” The French would write this as “Checagou.” 5

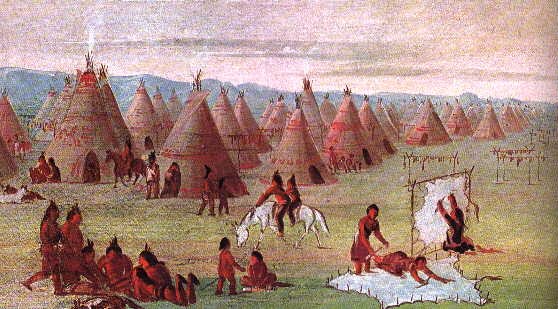

People indigenous to the region settled along the rivers. Villages and nations lived near Checagou and used the area as a crossroads for trade. Thousands of years span the history of the people that lived in the area. The massive bodies of water left over from the glaciers fostered the growth of the Great Lake Tribes.

The Great Lake Tribes

Evidence of human life in the area dates back as early as 10,000 B.C. Submerged underneath Lake Michigan is an ancient structure. Carved stones stretch for about one mile before culminating into a small circle. The structure, discovered in 2014, is believed to be an ancient hunting cabin6.

There are thousands of years worth of history that’s unrecorded. Making it difficult to pinpoint the first people to call the area around Chicago home. The marshland was not hospitable for life, although trading trails cut through the area. These trails were important for trade, many of which are still in use today as Chicago’s streets7.

The surrounding plains and river system became home to the local tribes. Life centered around farming. Villages dotted rivers, like the Fox River and Des Plaines River. To access Lake Michigan to connect with the other tribes, the locals used the only portage across the continental divide, the Chicago River which flowed into Lake Michigan8.

Many tribes used the area as a hunting ground and trade network. The Illinois, a confederacy of around 13 tribes, are one of the many that claim Chicago as part of their ancestral lands. The Miami, Fox, and Sauk all have ancestral ties to Chicago. The Council of Three Fires is an alliance of three tribes that have ties as well9.

The Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi were all one people when they lived on the east coast of North America. They traveled to Michilimackinac, the area around Mackinac Island, Michigan, and founded the Council in 796 A.D10. The Potawatomi lived in southwestern Michigan and Northeastern Illinois. They would be the last tribe that was forcibly removed from Chicago.

It’s with the Potawatomi we begin Chicago’s story.

Next time: The Potawatomi - Life Before European Contact

U.S. Census Bureau. “QuickFacts: Chicago City, Illinois.” U.S. Census Bureau. Last modified 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/chicagocityillinois/PST045223. ↩

Miller, Donald L. City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America. New York: RosettaBooks,2014. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Arkeonews. “The Mysterious Prehistoric Underwater Structure beneath Lake Michigan.” Arkeonews, December 3, 2021. https://arkeonews.net/the-mysterious-prehistoric-underwater-structure-beneath-lake-michigan/. ↩

Miller (2014). ↩

Keating, Ann Durkin. Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. ↩

Kubiak, William J. Great Lakes Indians: A Pictorial Guide. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House Company, 1970. ↩

Loew, Patty; "Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal"; Madison, Wisconsin Historical Society Press; 2001. ↩